In the mid-19th century, the city of Saint-Étienne in France was a bustling center of arms making. For generations, local gunsmiths had crafted firearms by hand, passing down artisanal skills through the ages. By the 1800s, two major innovations reshaped the firearms world. First came the shift from flintlock to percussion; then came the advent of the Lefaucheux breechloading system. Together, these changes dramatically altered not only the weapons themselves but also the labor economy of gunsmithing in Saint-Étienne. This is the story of how the Lefaucheux breechloader brought back a demand for fine craftsmanship that earlier technology had nearly put to rest.

Fleury Ronchard-Siauve was born in 1819 in Saint-Étienne and died there in 1878. A cannon manufacturer by trade, he opened his own gunsmithing workshop in 1840. By the 1860s, he had become a respected figure in the arms-making community of Saint-Étienne, with decades of firsthand experience in barrel manufacturing. In 1864, he published a detailed book titled Traité de la fabrication des canons de fusil, offering both a technical manual on how barrels were made and a broader reflection on the changing nature of gunsmithing in his time. His observations provide a valuable window into how firearms technology shaped the lives of the craftsmen who built them.

Flintlock Craftsmanship and the Rise of Percussion (Fewer “Limeurs” Needed)

Before percussion caps came along, making a firearm was a truly hand-crafted endeavor. A flintlock musket or pistol contained many intricate parts (pan, frizzen, springs, and the flint-holding hammer) that all had to fit together just right. Skilled metal filers, known in French as limeurs, were essential workers in the gun trade. These artisans spent long hours with files and scrapers, fine-tuning every surface so that the lock would function smoothly. As barrel maker Ronchard-Siauve recalled in 1864, crafting the old flintlock mechanisms “kept a great number of good filers” employed, since so much delicate fitting was required.

However, the introduction of percussion cap firearms (the fusil à piston) simplified the lock mechanism. The complicated flintlock assembly was replaced by a simpler percussion lock: just a hammer striking a percussion cap on a nipple to ignite the charge. Gunmaking became a bit more streamlined. Fewer parts and a more straightforward design meant less filing and hand-adjustment was needed in the factory. According to Ronchard-Siauve, “since the percussion gun replaced the flintlock, the number of good filers has rather decreased.” In other words, many of the fine filers found their specialized skills less in demand. The old hands had to adapt or risk being put out of work by the new, easier-to-make guns. Saint-Étienne’s arms industry was becoming more about quantity and interchangeability, and less about individual artisans crafting each piece.

The Lefaucheux Breechloader Brings Back Precision Craft

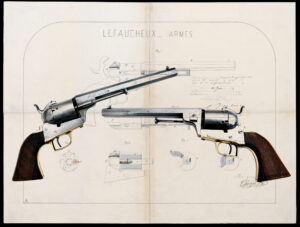

Then came the Lefaucheux breechloading system, a revolutionary firearm design that would once again demand high-precision work from Saint-Étienne’s gunsmiths. Invented by Casimir Lefaucheux and popularized in the 1850s and 1860s (notably by his son Eugène Lefaucheux), this system used self-contained pinfire cartridges and a break-open breech mechanism instead of the traditional muzzle-loading with ramrods. It was a major technological leap forward. But interestingly, in the workshop it meant going back to meticulous fitting and tight tolerances.

Early testimonials captured both enthusiasm and practical considerations around Lefaucheux’s innovation. J. Jovin, an influential gunsmith from Saint-Étienne, specifically highlighted how Lefaucheux resolved persistent mechanical shortcomings that Pauly and subsequent inventors had left unsolved, calling the hinge-breech a definitive advancement in firearm reliability and ease of use.

I have used Pauly’s gun for a long time and later those of Roux and Picherau. Each solved some problems yet left others. Of all the guns I have seen to date, M. Lefaucheux’s hinge-breech is the simplest, safest, and most convenient. I would gladly see this arm adopted, especially for light-infantry regiments.

J. Jovin, Proprietor, Manufacture royale d’armes de Saint-Étienne, 8 Jan 1835

Unlike a muzzle-loading percussion gun (which could have a bit of wiggle room in its components), a breechloading firearm needed precisely machined and fitted parts. The hinge that allowed the barrel to open, the locking lugs or levers that secured the breech closed, and the chambers for the cartridges all had to align perfectly to contain the force of the gunpowder. If the breech didn’t lock up exactly, the gun could leak gas or even burst. There was no room for sloppiness; this was precision engineering by the standards of the day. As a result, the manufacture of Lefaucheux guns “created some new skilled filers again,” according to Ronchard-Siauve. The tight-fitting parts revived the need for artisanal skills: seasoned limeurs and other craftsmen were once more in high demand to carefully file, fit, and finish the breech mechanisms. Saint-Étienne’s gun industry, which had been trending toward simpler work, suddenly found itself relearning the art of fine tolerances.

Since the percussion gun replaced the flintlock, the number of good filers has rather decreased. It is true that the Lefaucheux system has created some new ones again; for the fitting of the locks and closing mechanisms, much care and great experience are required.

Fleury Ronchard-Siauve, Traité de la fabrication des canons de fusil (1864)

One contemporary observer described the Lefaucheux breechloader as “a truly very handy weapon”, and that convenience was made possible by the painstaking handiwork of the gunsmiths who built it. The new system called for precision assembly at every step. Barrels had to meet the breech face without even a hairline gap. The locking action needed to snap shut with strength and exactness. Such tasks could not yet be done entirely by machines in the 1860s; they relied on the steady hands of expert workers. In effect, the breechloader brought back a measure of artistry and craftsmanship to gunmaking. Old-timers who had honed filing skills on flintlocks, or a new generation trained to tighter standards, now had an opportunity to shine.

From Hesitation to a New Standard

When the Lefaucheux system first started making waves in Saint-Étienne, not everyone jumped on board immediately. Change can be daunting, especially for craftsmen used to the percussion style. Ronchard-Siauve noted that initially even the local makers “had trouble getting into it”, as there was some reluctance and a learning curve in adopting the new breechloading design. This hesitation is easy to understand: the breechloaders were more complex to build, and required investments in new tools and training. Some gunsmiths may have worried that the effort wouldn’t pay off, or that hunters would not trust these novel guns that used strange pre-made cartridges.

But as the years went on, the advantages of the Lefaucheux system became impossible to ignore. By the early 1860s, it was “the fashionable gun”, very much in demand. Both the craftsmen and their customers came around to the new idea. In fact, Ronchard-Siauve observed that the Lefaucheux breechloader was rapidly replacing the old percussion (muzzle-loading) guns day by day. What had started as an innovation became the new standard.

Why did the gun community of Saint-Étienne ultimately embrace the Lefaucheux system? Simply put, it was a better experience for the shooter. The breechloading shotgun or rifle offered practical benefits that muzzle-loaders couldn’t match:

One could say this system gave rise to a more refined firearm, not by ornamentation, but by its construction and use.

Fleury Ronchard-Siauve, Traité de la fabrication des canons de fusil (1864)

In day-to-day use, these pinfire breechloaders proved more enjoyable and efficient for shooters. One could say they were a more “refined” breed of firearm, not because of ornamentation, but because of their modern design and ease of use. Hunters and soldiers alike began to appreciate how practical the new system was. And as demand for Lefaucheux guns grew, Saint-Étienne’s workshops thrived by meeting that demand with quality products. The gunsmiths who mastered the breechloading technology found their skills rewarded, and the city’s arms industry stayed relevant in a rapidly evolving market.

By the late 1860s, even the traditionalists had largely come around. The Lefaucheux breechloader and its successors were here to stay, setting the stage for the metallic cartridge firearms that would dominate the future. What’s especially interesting is how this technological advance rebalanced the labor force in the gun industry. The move from flintlock to percussion had briefly reduced the need for the old-school filers and fitters, but the breechloader brought them back into prominence. In the end, the innovation didn’t deskill the trade; it re-skilled it. Saint-Étienne’s identity as a hub of fine arms making was preserved, as the craftsmanship of its workers once again became the key to producing the best guns.

The Lefaucheux system’s success in Saint-Étienne is a prime example of how advances in firearms could transform the workshop as much as the battlefield. A new gun design changed the fortunes and daily work of the people building them. And in this case, progress meant rekindling the artisanal heritage of gunsmithing in one of Europe’s great arms-making cities. The breechloader era proved that even as guns became more modern, the skilled touch of the craftsman was still very much needed and valued.

Today, Saint-Étienne’s reputation as a cradle of fine arms owes much to the craftsmen who mastered not just flint and percussion, but the precision demands of the breechloader.

References

Ronchard-Siauve, Fleury. Traité de la fabrication des canons de fusil. Saint-Étienne: impr. de Vve Théolier aîné, 1864. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Littérature et art, V-51873. Public domain. https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb31241676t